Hans Bollongier, a notable painter of the Dutch Golden Age, carved a distinct niche for himself with his vibrant and expressive floral still lifes. Active primarily in Haarlem during the 17th century, his work provides a fascinating window into the artistic trends, societal interests, and even the economic phenomena of his time, particularly the infamous "Tulip Mania." While perhaps not as universally acclaimed in his own era as some of his contemporaries specializing in historical or portrait painting, Bollongier's contributions to the still life genre are now recognized for their unique stylistic qualities and historical significance.

The Artist's Life and Times: Navigating the Dutch Golden Age

The precise details of Hans Bollongier's birth and death remain somewhat debated among art historians, a common challenge with artists from this period. He is generally believed to have been born around 1598 or 1600, possibly in The Hague, though he is most strongly associated with the city of Haarlem, where he spent the majority of his working life. His death is recorded as occurring sometime between 1672 and 1675. This places his activity squarely within the Dutch Golden Age, a period of extraordinary economic prosperity, scientific advancement, and artistic flourishing in the newly independent Dutch Republic.

Bollongier became a member of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke in 1623. This membership was crucial for any artist wishing to practice professionally, take on apprentices, or sell their work within the city. Haarlem, at this time, was a vibrant artistic center, home to renowned painters across various genres. While figures like Frans Hals were revolutionizing portraiture with their lively and characterful depictions, and landscape artists such as Jacob van Ruisdael and Salomon van Ruysdael were capturing the Dutch countryside with unprecedented realism, a burgeoning market also existed for still life paintings.

The rise of a wealthy merchant class, eager to adorn their homes with art, fueled demand for diverse subjects. Still lifes, with their depictions of everyday objects, luxurious items, or natural wonders like flowers, appealed to this new patronage. Within this context, Bollongier specialized, becoming one of Haarlem's few dedicated painters of flower bouquets. A personal detail that has survived is that in 1675, shortly before or around the time of his death, he designated his brother, Horatio (or Horio) Bollongier, as his beneficiary, offering a small glimpse into his personal affairs.

The Artistic Milieu of Haarlem and Still Life Traditions

Haarlem in the 17th century was a crucible of artistic innovation. The city's painters were known for their naturalism and their focus on subjects drawn from the world around them. In the realm of still life, artists like Pieter Claesz. and Willem Claesz. Heda became masters of the ontbijtje (breakfast piece) or monochrome banquet scenes, showcasing their skill in rendering textures of pewter, glass, and foodstuffs with subtle tonal harmonies. Earlier Haarlem still life painters like Floris van Dyck and Nicolaes Gillis had already laid groundwork for elaborate table settings.

Flower painting, as a distinct subgenre of still life, had its roots in the works of artists like the Flemish master Jan Brueghel the Elder, whose detailed and jewel-like floral arrangements were highly influential across the Netherlands. In the Dutch Republic itself, pioneers such as Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder and his brother-in-law Balthasar van der Ast, working primarily in Middelburg and Utrecht, established a tradition of meticulously rendered, often symmetrical bouquets featuring rare and exotic blooms. These early flower pieces were characterized by their bright illumination, precise detail, and often symbolic content, with flowers chosen not just for their beauty but also for their allegorical meanings related to transience (vanitas), divine creation, or national pride.

Bollongier entered this evolving tradition, but he brought his own distinct approach to the canvas, differentiating himself from the more polished and minutely detailed style of many of his predecessors and contemporaries.

Bollongier's Signature Style: Chiaroscuro and Expressive Brushwork

Hans Bollongier's artistic style is most notably characterized by his use of strong chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow. This technique, often associated with Italian masters like Caravaggio and adopted by Dutch artists such as Rembrandt van Rijn in different contexts, allowed Bollongier to create a sense of depth and volume in his floral arrangements. His flowers often emerge from deeply shadowed backgrounds, their forms sculpted by a focused light source, lending them a theatrical and dynamic presence.

Another hallmark of Bollongier's work is his relatively bold and often looser brushwork compared to the refined, almost invisible brushstrokes of artists like Bosschaert or, later, Rachel Ruysch. While still capable of rendering detail, Bollongier's application of paint could be more vigorous and expressive, giving his flowers a sense of vitality and movement. This approach sometimes led to a less polished finish, which might have contributed to the contemporary assessment by some of his peers that his work was less refined than that of other still life specialists. However, this very quality now contributes to the unique appeal of his paintings, imbuing them with an energetic immediacy.

He predominantly focused on floral subjects, with tulips, roses, carnations, irises, and narcissi frequently appearing in his compositions. These were often arranged in simple earthenware or glass vases, allowing the focus to remain firmly on the blooms themselves. His compositions, while sometimes dense, often possess a certain asymmetry and dynamism that distinguishes them from the more formally structured bouquets of earlier flower painters.

Tulips, Mania, and Artistic Documentation

A significant aspect of Bollongier's oeuvre is his depiction of tulips, which holds particular historical importance due to its connection with "Tulip Mania" (Tulpenmanie). This speculative bubble, which gripped the Netherlands primarily in the 1630s (peaking around 1634-1637), saw the prices of rare tulip bulbs reach astronomical heights before the market dramatically crashed. Tulips, especially those with variegated patterns caused by a virus (though not understood as such at the time), became symbols of wealth, status, and speculative folly.

Bollongier painted numerous works featuring tulips during and after this period. His paintings serve as a visual record of the types of tulips that were prized, such as the "broken" tulips with their feathered or flamed petals. While it's unlikely his paintings were intended as direct critiques of Tulip Mania in the way some satirical prints of the era were, they undoubtedly catered to a public fascinated by these flowers. The inclusion of rare and expensive tulip varieties in a still life would have signaled the owner's taste, wealth, or at least their aspiration to it.

Art historians now view Bollongier's tulip paintings as important documents of this peculiar socio-economic phenomenon. They capture the beauty of the flowers that drove a nation to speculative frenzy, immortalizing blooms that were, by their very nature, ephemeral. His focus on these specific flowers, rendered with his characteristic vigor, makes his work a key reference point for understanding the visual culture surrounding Tulip Mania.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

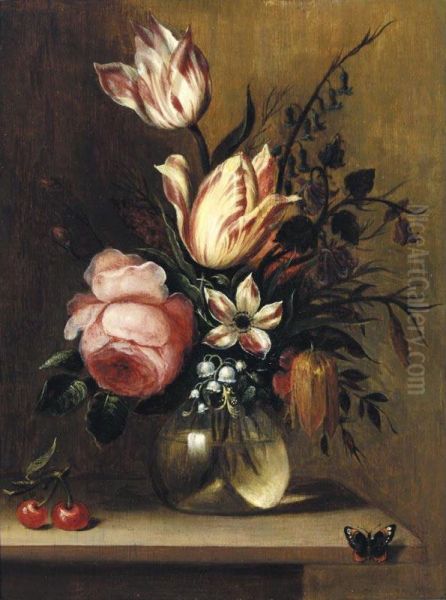

One of Hans Bollongier's most well-known paintings is the Floral Still Life (sometimes titled Still Life with Flowers or Flower Piece), dated 1639, now housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. This oil on panel, measuring approximately 67.6 x 53.3 cm, exemplifies many of his stylistic traits. A vibrant bouquet, dominated by red-and-white and yellow-and-red variegated tulips, alongside roses, irises, anemones, and other flowers, bursts forth from a simple, dark earthenware vase.

The composition is dynamic, with flowers at various angles and stages of bloom, some reaching upwards, others gently drooping. The background is dark and undefined, characteristic of his use of chiaroscuro, which makes the brightly lit flowers stand out dramatically. The brushwork is confident and visible, particularly in the rendering of the petals, conveying their texture and form without excessive detail. Small insects, like a butterfly or a beetle, are often included in his works, common motifs in Dutch still life that could symbolize transience or the beauty of God's creation.

Other works by Bollongier, such as his Still Life of Tulips, Roses, Narcissi, Carnations and other flowers in a glass vase on a stone ledge (c. 1627-1630), showcase similar characteristics. His consistency in subject matter and style makes his hand relatively recognizable. While he primarily painted flowers, occasional fruit still lifes are also attributed to him, though these are less common.

Interactions and Standing Among Contemporaries

Direct records of Hans Bollongier's specific interactions or collaborations with other named artists are scarce. However, as a member of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, he would have been part of a community of artists, sharing knowledge, competing for commissions, and undoubtedly aware of each other's work. His specialization in flower painting set him apart from the city's more numerous portraitists, landscapists, and genre painters like Adriaen Brouwer or Adriaen van Ostade, who depicted peasant life with earthy realism.

It is noted that in Haarlem, as in many artistic centers of the time, history painting (depicting biblical, mythological, or historical scenes) was generally held in the highest esteem within the academic hierarchy of genres. Still life, despite its popularity with the buying public, was often ranked lower. This might explain why some contemporary accounts or guild records might not have lauded Bollongier with the same fervor as, for example, a history painter like Pieter de Grebber.

Nevertheless, the demand for his floral pieces indicates a significant market appreciation. His style, while distinct, existed within a broader context of Dutch still life painting. He would have been aware of the more polished works of artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, who became famous for his opulent and highly detailed "pronkstilleven" (ostentatious still lifes), or the earlier, more restrained flower pieces of Roelandt Savery. Bollongier's approach offered an alternative, perhaps appealing to patrons who favored a more robust and less formal aesthetic.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

While perhaps not as broadly influential as some of the towering figures of the Dutch Golden Age, Hans Bollongier's work did leave a mark. His distinctive style is believed to have influenced a few later artists, including the monogrammist "JF" and Anthony Claesz. II (also known as Anthonie Claessens de Jonge), who also specialized in flower paintings. His focus on the dramatic potential of floral arrangements and his expressive technique provided a model for artists seeking to move beyond purely descriptive renderings.

In the longer arc of art history, Bollongier's paintings contribute to the rich tapestry of Dutch still life. His works are valued today not only for their aesthetic qualities but also as historical documents. They reflect the Dutch fascination with horticulture, the economic story of Tulip Mania, and the broader cultural values of the Golden Age that celebrated the beauty of the observable world.

Modern scholarship has increasingly recognized the importance of artists like Bollongier, who, while perhaps not innovators on the scale of Rembrandt or Vermeer, played a vital role in shaping the character and diversity of Dutch art. His paintings are regularly included in exhibitions on Dutch Golden Age art and floral still life, ensuring his contribution is appreciated by contemporary audiences. The very fact that his works are sought after by museums and collectors today attests to his enduring appeal.

Historical Evaluation and Conclusion

In summary, Hans Bollongier was a significant Dutch Golden Age painter who specialized in floral still lifes, particularly those featuring tulips. Active in Haarlem from the 1620s until his death around 1672-1675, he developed a distinctive style characterized by strong chiaroscuro, bold brushwork, and dynamic compositions. His membership in the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke placed him within a thriving artistic community that included masters like Frans Hals and Jacob van Ruisdael, though his chosen genre of still life occupied a different, if popular, niche.

His paintings, such as the 1639 Floral Still Life in the Rijksmuseum, serve as important visual records of the prized flowers of his time, most notably the tulips associated with the Tulip Mania phenomenon. While contemporary esteem among some peers might have favored other genres, Bollongier's work found a ready market and has since been recognized for its artistic merit and historical value. He influenced a subsequent generation of flower painters and remains an important figure for understanding the breadth and depth of still life painting during one of art history's most fertile periods. His legacy is that of an artist who captured the ephemeral beauty of flowers with a unique energy and dramatic flair, leaving behind a body of work that continues to engage and fascinate.